Saturday, April 18, 2009

Chinese Performance Arts

what are considered most popular.

The program of that evening covered two broad areas: Music (including Opera) and Dance. I can’t say much about dance since I am pretty ignorant about it. I did enjoy very much the choreography by Nai-Ni Chen and the performance by her award winning Dance Company that she founded over 20 years ago. With her modern dance creation of Five Elements – Fire, one can see the influence of legendary Cloud Gate Dance Theatre 雲門舞集in Taiwan where she was a featured principal dancer.

The traditional Chinese music was presented in several performances by a 6 musician ensemble and solos. The ensemble was made up of six Chinese music instruments: DiZi笛子, Erhu 二胡, Yangqin 揚琴, Pipa 琵琶, Ruanqin 阮琴, and Guzheng 古箏. I am sorry to say that I don’t know much about traditional Chinese music either and listen to it only sparingly. But it should not be surprising to you that there is a long history of Chinese music. It is well-established over 3000 years ago and its development has received significant influences from Central Asia 1500 years back. Instruments like Erhu and Pipa are good examples.

What is true though is that listening to Chinese classical music is a totally different experience from the Western (i.e. European) one. To begin with, the two have completely distinct frameworks and scales. In technical terms (see e.g., a discussion website at Wake Forest University), Chinese music mainly uses five 5 note base scales - gong, shang, jue, zhi, yu宮商角徵羽, while Western music has been dominated by the familiar seven note diatonic scales. Further, western music theory emphasizes on harmonics and ability to play many keys without many sets of instruments. In contrast, Chinese music pays much more attention to melodic line and linear quality or the progression.

One fun and quick way of getting an appreciation is to watch and hear the most popular Pipa solo score Ambush from Ten Side十面埋伏. The following YouTube video was performed by Master Liu DeHai刘德海. Some have compared this masterpiece to Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Flight of the Bumblebee in Western music (you may recall it was featured in the 1996 movie Shine and played in piano). Both have high degree of difficulty and can only be performed well by virtuosos.

A big part of the Chinese Performance Arts is Chinese Opera that has been popular for at least one thousand years and comes in different flavors from different regions of the country. The program presented two performances in Peking Opera京劇and one in KunQu Opera 崑曲. The latter is of particular interest and significance. Kun Opera is considered by many the mother of Chinese Operas of the last 500 years and has dominated the Chinese theatre between 16th and 18th century. It has also had significant influences on Peking Opera that has been more popular in last two centuries. What separates KunQu from others and Western Opera is its simultaneous emphasis and attention to the librettos, arias, acting, hands and body movement, completed with elaborate headgears and costumes; it is an unparallel art form with an intricate and elegant combination of literature, drama, music, and dance!

The evening was highlighted with a Kun Opera performance by two 68 year-old superstars Cai ZhengRen蔡正仁 and Zhang XunPeng 張洵澎of the Shanghai Kun Opera Theatre上海昆劇團. They performed a portion of the scene Disrupted Dream 驚夢 of The Peony Pavilion 牡丹亭, a masterpiece by Ming Dynasty playwriter Tang Xianzu 湯顯祖(1550-1616). The complete play is about a beautiful love story (what else!) and consists of 55 scenes and takes about 20 hours to perform. In comparison, the monumental 4 parts epic opera Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung) by the German composer Richard Wagner is about 15 hours long (and is also rarely performed in its entirety). By the way, Tang XianZu was a contemporary of William Shakespeare. He completed this play in 1598, the same year Shakespeare wrote his Henry IV, Part II and Much Ado About Nothing. Some western scholars have considered this play the Chinese Romeo and Juliet that seems too much a cliché. Given the strict social and moral code of the time, this play was in fact radical and was a powerful and explicit challenge to the tradition and custom of arranged marriage.

Kun Opera had lost its attraction for some time and was nearly wiped out in China during the Culture Revolution. In his successful effort of rejuvenating Kun Opera, famous writer and Professor Bai Xianyong 白先勇and a group of scholars and performers adapted and edited the original script of The Peony Pavilion down to 27 scenes and 9 hours long. This so called Youth Edition was premiered in 2004 in Taiwan and later in China and U.S. with great success. It has been credited for the renewed interests and excitement about Kun Opera across the world. I think Professor Bai has accomplished his goal “ to give new life to the art form, cultivate a new generation of KunQu aficionados, and offer respect to playwright Tang and all the master artists that came before."

For your enjoyment, I managed to find on Youtube a short performance by Cai ZhengRen蔡正仁 and Zhang XunPeng 張洵澎of a portion of the Disrupted Dream. Here it is.

Before I go, I must mention another special treat of the evening: the curious Chinese magic of Face-Changing變臉 (or Face Off, remember that 1997 movie of that title?). It was and still is a part of Sichuan opera 川劇but often performed as a stand-alone magic show nowadays. This art is not as well-known outside China and has rarely been seen in U.S. One reason might be that this special skill is a tightly guarded trade secret that has been passed down mostly within male members of the families of masters.

That evening, Master Peng Li demonstrated the change of a dozen or so masks, each in a whim within a split second (the fastest world record is presumably three mask changes in one second!. Like many audience of magic shows, I couldn’t help but guessing how it was done and if these masks were initially placed on top of each other. Then the trick would boil down to how quickly one can remove one at a time and tuck it away. Just as I was speculating with myself, Master Li took one more mask off and revealed himself. Next second, as if he had seen through my mind of my question, he put back a mask on his face! Um, how does he do that? What a fantastic entertainment and illusion!

If you can’t make it to a life performance of Face-Changing, I recommend you see a very nice Chinese movie called The King of Masks 變臉. The story is about the relation of a Master of this very performance art and a little girl who aspired to become a master. If you can’t get hold of this movie, you can go to YouTube and find quite a few videos of it although the quality of them is not that good. Here is one for your convenience. Talk to you soon!

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

Museum Art Collections and Cultural Heritage

Every time when friends and families come to visit, it is a great opportunity for me to reacquaint with some amazing art works in museums of the area. Recently, I had a chance to visit the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia and the Met (Metropolitan Museum of Arts) in New York City.

Rodin Museum, as its name suggests, is dedicated to work by the famous French Sculptor Auguste Rodin. The building and its contents was a gift to the city by Jules Mastbaum, a not so-well-known Philadelphia based movie theater magnate and philanthropist. This tiny museum sits quietly off the fabulous Benjamin Franklin Parkway and is only a stone-throw away from the massive and popular Philadelphia Museum of Art.

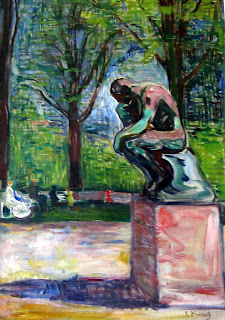

At the entrance to the courtyard and building, there stands the most well-known sculpture of the world by Rodin in 1880 – The Thinker (if you have seen it at other places, it is because there are 61 of it cast from the original mold). It is so special because it captures not only the essence of human thinking but, as Rodin  himself put it, “What makes my Thinker think is that he thinks not only with his brain, with his knitted brow, his distended nostrils, and compressed lips, but with every muscle of his arms, back, and legs, with his clenched fist and his gripping toes.” By the way, to get another angle of “The Thinker”, here is a photo of the oil painting of Rodin's the Thinker by the revered Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (you may have seen or heard of his most famous work The Scream) that is now with the Louvre in Paris.

himself put it, “What makes my Thinker think is that he thinks not only with his brain, with his knitted brow, his distended nostrils, and compressed lips, but with every muscle of his arms, back, and legs, with his clenched fist and his gripping toes.” By the way, to get another angle of “The Thinker”, here is a photo of the oil painting of Rodin's the Thinker by the revered Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (you may have seen or heard of his most famous work The Scream) that is now with the Louvre in Paris.

Rodin’s other most famous works include The Burghers of Calais, The Gates of Hell, and The Kiss. A cast of the first two are available for viewing in the museum with The Gates of Hell placed right at the front of the building. But the most intriguing work for me is “The Secret”;  for your convenience, I include a photo here from Adam Fagan’s Flickr page. This is one of several distinct hand expressions in Rodin’s study for Secret that I thought is the best among all. The two right hands are engaged in a conversation in silence. What are they saying to each other with that peculiar gesture? Are they exchanging a secret? Or are they trying to tell each to keep a secret? By not saying a word or write a letter, the artist conveyed such a rich expression in grace and left so much for us to our imagination!

for your convenience, I include a photo here from Adam Fagan’s Flickr page. This is one of several distinct hand expressions in Rodin’s study for Secret that I thought is the best among all. The two right hands are engaged in a conversation in silence. What are they saying to each other with that peculiar gesture? Are they exchanging a secret? Or are they trying to tell each to keep a secret? By not saying a word or write a letter, the artist conveyed such a rich expression in grace and left so much for us to our imagination!

Few days earlier, we visited The Met (Metropolitan Museum of Art) in New York City, one of the largest museums and art galleries of the world with more than 2 million items of art collections of practically all major civilizations in 2 million square feet. In contrast, Rodin museum has about 100+ pieces of sculptures in approx 5,000 square feet.

The Met has an impressive collection of Asian arts, among others. Its collections of Chinese Arts are of exceptionally high quality that sooth Chinese American’s home sickness a little bit and introduce to others treasures from a major civilization. Unlike Rodin Museum's, there are controversies with some of its collections however.

If you stop by the 2nd floor galleries for Asian Collections, you will not miss the monumental Chinese stone sculptures from the fifth through the eighth century (Northern Wei 460-525 AD to Tang dynasty) in Arthur Sackler Gallery. As you enter the gallery, what catches everyone’s eyes is a huge mural over 30 ft tall from Yuan Dynasty about 900 years ago. The real priceless treasure is on the opposite wall, a 1500 years old embossed stone sculpture of Worship of Buddha by Northern Wei Emperor XiaoWen 北魏孝文帝禮佛圖 that was removed illegally from Guiyang Cave of the Longmen Grottoes 龍門石窟 in Henan Province of China sometime late 19th century and ended up with The Met. Similar examples can be found at several major museums in U.S., Great Britain, France, etc.

While I appreciate very much the opportunity to enjoy the precious arts, this begs the question of how did cultural treasures like this end up outside their home country? Have the museums done enough to avoid acquiring stolen objects? How many of them and which ones were acquired illegally? Indeed, by UNESCO’s estimate, about 1.67 million pieces of Chinese relics have been collected by two hundred museums across 47 countries. It is also believed that there could be 10 times more relics are in private collectors’ hands across the world. It is a massive and challenging undertaking to acquire the corporations and sort out the information even just for a small portion of them.

The recent auction incident at Christie’s for a pair of bronze animal heads 圓明園獸首 from collections of the late fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent Yves Saint Laurent and his partner Pierre Berge served all of us a reminder. These are rat’s and rabbit’s heads in bronze, two of the sculptures made for the Zodiac fountain of the Emperor Qianlong's Summer Palace, aka Old Summer Palace and YuanMing Garden, in mid 18th century under the supervision of by the Italian Jesuit priest Giuseppe Castiglione 郎世寧. They appear to have been looted during the Second Opium War in 1860 when about 20,000 British and French troops invaded Beijing, looted the palaces and burned down the Old Summer Palace. The auction ended with a bid from a Chinese collector for over 14 million Euros each. However the transaction was never completed as the buyer indicated that he has no intention to complete the transaction and that the bidding is a part of an effort in seeking the return of the stolen objects to China.

This obviously is not an isolated case or issue and is not limited to Chinese. There are plenty of examples, past, current, and no doubtedly in the future whenever there are corruptions, chaos, and wars in any corner of the world. The 2006 book of Art and Cultural Heritage: Law, Policy, and Practice by Barbara Hoffman has extensive discussions of this very topic from legalistic perspectives. It is impractical to believe like some with patriotic and nationalistic fever that one can get the lost objects back unilaterally and quickly somehow. Persistent multi-pronged approach is needed in economic, political and legal fronts with coordinated government and private efforts. What is encouraging is the very first step of systematic investigation and documentation of lost objects has begun in China, according to some reports. We look forward to seeing more rigorous record keeping and return of cultural treasures to their rightful owners one day, along with frequent exhibits in musuems worldwide under loan.

Talk to you soon!